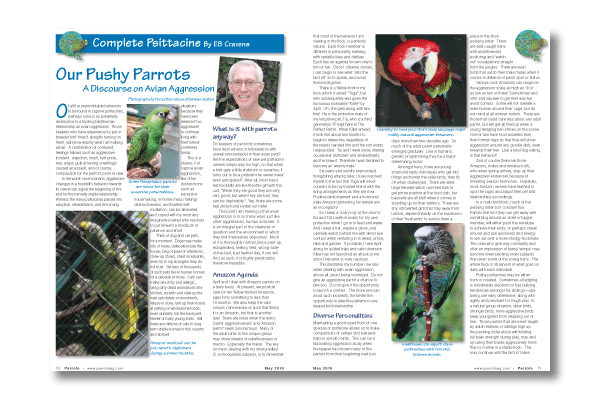

Our Pushy Parrots - A Discourse on Avian Aggression

Of all the unpredictable behaviors to be found in captive psittacines, perhaps none is as potentially destructive to a trusting bird/human relationship as avian aggression. Those keepers who have experienced a pet or breeder bird ‘friend’ abruptly turning on them, will know exactly what I am talking about. A combination of confused feelings follows such an aggressive incident: dejection, insult, hurt pride, fear, anger, guilt at having unwittingly caused an assault, and of course, compassion for the parrot’s point of view.

In the worst-case scenario, aggressive changes in a hookbill’s behavior towards its owner can signal the beginning of the end for the formerly stable relationship. Witness the many psittacines placed into adoption, rehabilitation, and re-homing situations because they have been deemed ‘too aggressive’ to continue living with their former contented family.

This is a shame. For captive avian aggression, like other dysfunctions such as excessive noisemaking, in-home mess making/destructiveness, and feather self-mutilation, can be alleviated and coped with by most any imaginative owner who resolves to put forward a modicum of patience and effort.

Read more in the magazine…

Buy a copy now!

BACK

Dairy Products and Parrots

Why are we so compelled towards sharing our favorite foods with our birds? It’s fun. It’s a bonding ritual. It’s also so cute the way they hold those precious tasty morsels in their feet! Sharing food with our birds is enjoyable and it feels good.

When discussing favorite foods, I’ll jump right to the point. Which type of cheese is your favorite? Whether it’s freshly grated parmesan, spicy pepper jack, or that richly decadent brie. I think we enjoy sharing cheese with our birds because we love it so much.

Being people, we’re mammals. We suckled at our Mother’s breast. And for so many of us cheese is a comfort food. But birds never suckled. They can’t, they don’t have lips. And more importantly, their physiology was never designed to consume any type of milk product. Do you know why? One word - lactase!

Birds completely lack the digestive enzyme, lactase, that is required to hydrolyze (break down) lactose, the disaccharide contained in milk, into its components of glucose and galactose - both simple sugars, monosaccharides. Because of this, milk is a very poor energy source and poor food choice for birds.

Read more in the magazine…

Buy a copy now!

BACK

Parent rearing: the way forward

Laney Rickman talks to Pauline James

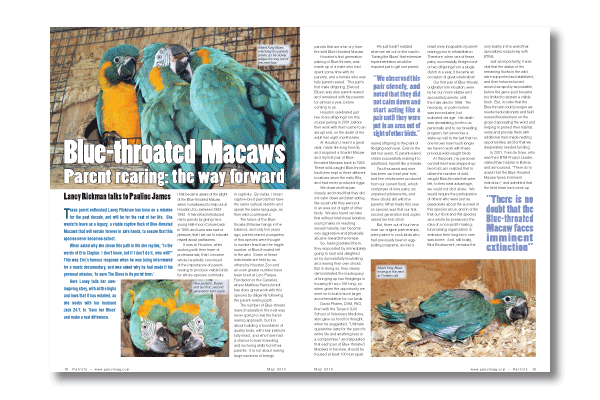

Texas parrot enthusiast Laney Rickman has been on a mission for the past decade, and will be for the rest of her life. She wants to leave as a legacy, a viable captive flock of Blue-throated Macaws that will remain forever in safe hands, to ensure that this species never becomes extinct.

When asked why she chose this path in life she replies, “In the words of Eric Clapton: I don’t know, but if I don’t do it, who will?” This was Eric’s famous response when he was being interviewed for a music documentary, and was asked why he had made it his personal mission, ‘to save The Blues in its purist form.’

Here Laney tells her awe-inspiring story, with all the highs and lows that it has entailed, as she works with her husband Jack 24/7, to ‘Save her Blues’ and make a real difference.

I first became aware of the plight of the Blue-throated Macaw when I volunteered to help out at Houston Zoo, between 1992-1993. A friend had introduced me to parrots by giving me a young Half-moon Conure back in 1990, and Luna was such a pleasure, that I set out to educate myself about psittacines.

It was at Houston, while working with their team of professionals, that I became whole-heartedly convinced of the importance of parent-rearing to produce viable birds for whole-species continuity in captivity. By viable, I mean captive-bred parrots that have the same cultural identity and speak the same language, as their wild counterparts.

Read more in the magazine…

Buy a copy now!

BACK

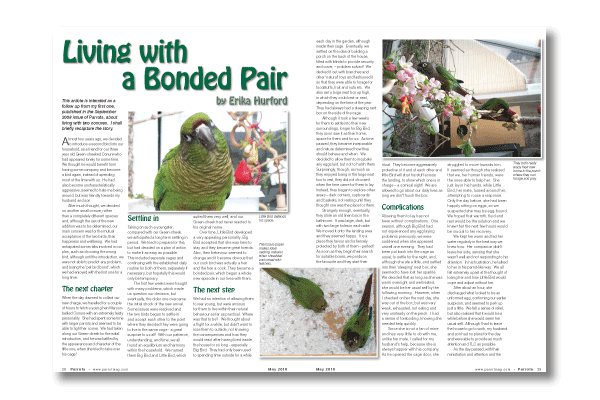

Living with a Bonded Pair by Erika Hurford

This article is intended as a follow up from my first one, published in the September 2008 issue of Parrots, about living with two conures. I shall briefly recapture the story.

Almost four years ago, we decided to introduce a second bird into our household, as a friend for our three year old Green-cheeked Conure who had appeared lonely for some time. We thought he would benefit from having some company and become a bird again, instead of spending most of the time with us. He had also become uncharacteristically aggressive, seemed to hate me being around, but was friendly towards my husband and son.

After much thought, we decided on another small conure, rather than a completely different species and, although the sex of the new addition was to be determined, our main concern was for the mutual acceptance of the two birds, their happiness and wellbeing. We had anticipated some risks involved in our plan, such as choosing the wrong bird, although until the introduction, we were not able to predict any problem, and losing the 'pet bird bond', which we had enjoyed with the first one for a long time.

Read more in the magazine…

Buy a copy now!

BACK