The Holistic Parrot by Leslie Moran

In ancient societies, primarily in Greece, China and Egypt, bee pollen and honey were well known for being used as medicine for healing. But with our planet becoming more polluted each year it’s essential that we considered pesticides and other toxic residues in the foods we choose to feed our parrots and eat ourselves. Herein we’ll explore the benefits and concerns of bee pollen and reveal a surprising gift that it offers the bees.

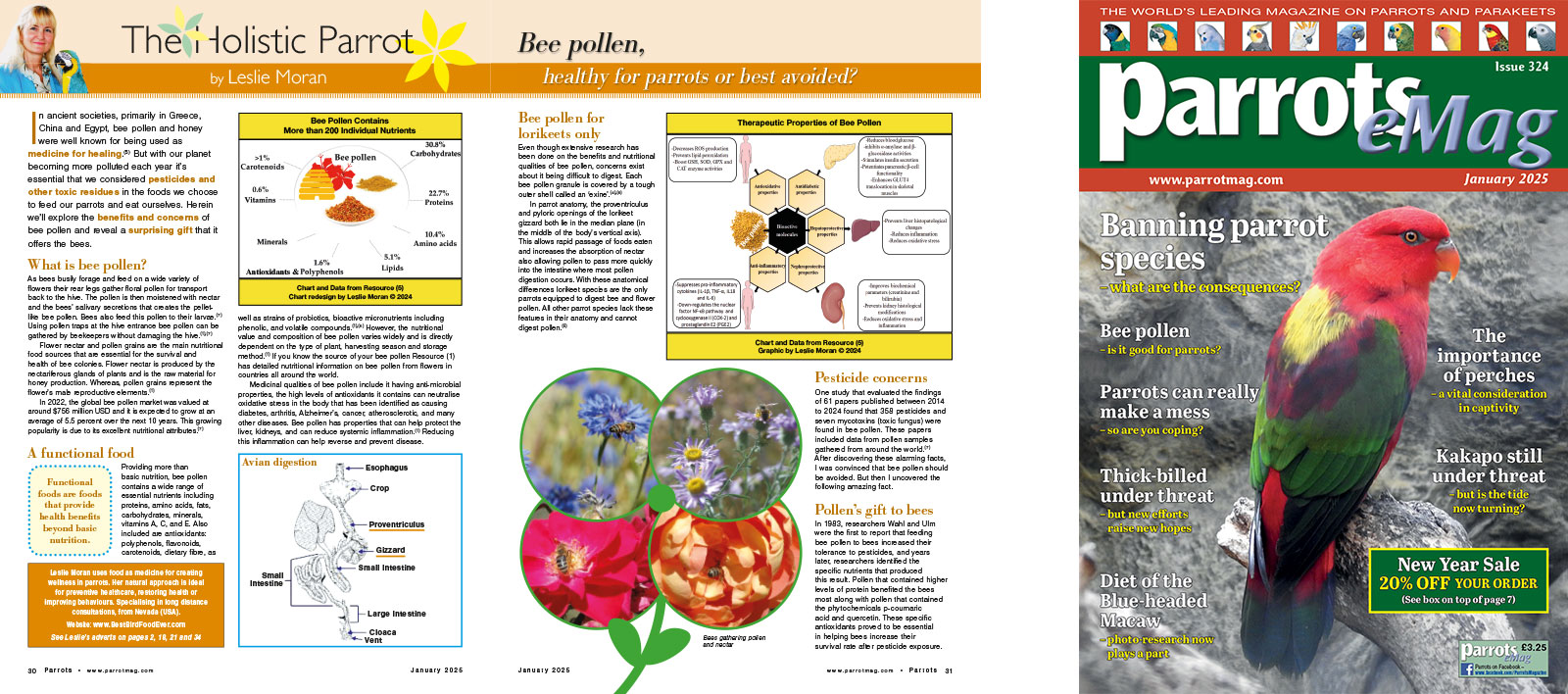

As bees busily forage and feed on a wide variety of flowers their rear legs gather floral pollen for transport back to the hive. The pollen is then moistened with nectar and the bees’ salivary secretions that creates the pellet-like bee pollen. Bees also feed this pollen to their larvae. Using pollen traps at the hive entrance bee pollen can be gathered by beekeepers without damaging the hive.

Flower nectar and pollen grains are the main nutritional food sources that are essential for the survival and health of bee colonies. Flower nectar is produced by the nectariferous glands of plants and is the raw material for honey production. Whereas, pollen grains represent the flower’s male reproductive elements.

Get your copy now

By Rosemary Low

In May 1930 a ban on the importation of parrots into the UK was brought into force. It had arisen due to psittacosis being found in Amazon parrots. Cases of psittacosis were reported in mid-1929, in Birmingham in the United Kingdom, and linked to parrots from Buenos Aires, Argentina, where an ongoing outbreak of the disease had occurred. The disease can be transmitted to humans and 14 people in the UK population of 39 million died soon after as a result. It threw the country into a panic and sadly many parrots were killed or even released.

In the early and mid-20th century, David Seth-Smith was curator of several important private bird collections. He eventually became the curator of birds and mammals at London Zoo and his book, entitled Parrakeets, a Handbook to the Imported Species (1926), was important. A frequent contributor to the Avicultural Magazine, in 1940 he wrote in that journal (page 288) about the effect of the ban a decade later. He commented: “I think we may say that the three main results have been the great increase in the keeping of parakeets, the very considerable progress made in the technique of keeping and breeding them, and the absurd levels to which the price of quite common parrot-like birds has risen.”

Up to 1930, most parrots were bought as pets or for mixed collections in aviaries, often quite large ones. Mortality was high and breeding results were few. Seth-Smith noted: “As Belgium was one of the few countries where no such ban was imposed, the result was, not a severe plague of psittacosis, but merely that prices went down and all sorts of very interesting psittacine birds turned up, in spite of the absence of specialist collectors, such as we have here.” No doubt these rarities would have otherwise gone to dealers in the UK or the Netherlands. He wrote that in Holland the ban was removed in early 1939. When it was still in force, birds were occasionally carried over the frontier at a marshy, foggy spot where the Customs and other frontier officials, for reasons of health, did not care to linger in the night air.

Get your copy now

By Sarah Lazarus

Kakapo are avid walkers, wandering on strong legs for miles at a time and hiking up mountains to find mates. They’re keen climbers too, clambering up New Zealand’s 65-foot-high Rimu trees on large claws to forage for red berries on the tips of the conifer’s branches. But there’s one thing that the world’s heaviest parrot species can’t do, and that is to fly. With their bulky frames, males can weigh up to nine pounds and a waddling gait, so have little chance of outrunning predators like stoats and feral cats. When threatened, the nocturnal parrots freeze, relying on their moss-green feathers to act as camouflage.

New Zealand was once a land of flightless birds like the extinct moa with no terrestrial mammalian predators in sight. That changed in the 13th century, when Māori voyagers brought rats and dogs, and again in the 19th century, when European settlers brought rats, cats and mustelids like weasels, stoats and ferrets. These predators have played a major role in putting at risk some 300 native species on New Zealand’s two main islands and smaller offshore islands, taking an especially heavy toll on flightless birds like Kakapo.

Now listed as critically endangered, the Kakapo teetered on the edge of extinction in the mid-1900s due to hunting, predators and land clearance. From the 1970s, conservation efforts focused on managing the remaining Kakapo on the country’s offshore islands, where predators were systematically eradicated. Due to those ongoing efforts, which include breeding programmes, veterinary treatment and supplementary food, Kakapo numbers have grown from fewer than 60 in 1995 to more than 200 today.

Get your copy now

Complete Psittacine by Eb Cravens

One hectic breeding season, we were coping with two 15-week-old Fuscicollis Cape Parrots fledging and weaning in our tiny three room farm cottage. The ‘kids’, Princess and Peter are all over the place, from that bright branch-filled garden window in the kitchen to their sleeping baskets and hanging rope perches on the sun deck. At this life stage they seemed to alternate between eating, napping, flying around squealing crazily, and chewing anything organic in sight. Flowers, beet stems, lime boughs, wood sticks, radish seed pods, along with beans and sprouts, corn on the cob and slabs of fresh papaya, citrus or pomegranate are all part of their fare. It’s really gratifying to see them so curious, learning new things at a rapid pace.

The exasperating side of the situation was we keepers constantly have to be cleaning up after the little ruffians. I have old bed sheets spread out everywhere, newspaper and plastic trays beneath their baskets, paper towels where they sleep at night. I declare, some mornings I will shake and wipe everything down, rearrange it neatly, and in thirty minutes or less we have another pile of chewed greenery, spit out corn, wiped off apple mush, dropped playthings, and of course poop! The rechargeable canister vacuum has become my new favourite friend.

For some reason the Cape Parrots I have known and raised take a sinister delight in picking things up and dropping them to the floor, the ground, or wherever else they can figure. Hens and cocks alike give that familiar twisted-neck, one-eye-pointed-downward stare at the object they have just released from beak or claw. Plop, bang, rattle, bounce. I seem to spend a lot of time picking up stuff with these intelligent parrots.

Get your copy now