Complete Psittacine by Eb Cravens

Whenever I am asked about bird caging, I usually respond with an opinion that the larger the enclosure for our parrots, and other birds, the better. I have known breeders who talked about their ‘aviaries’ where the birds were housed, but when I ask about dimensions, they show me photos of 4ft x 4ft cages in which African Greys and other Amazon sized psittacines are being housed. That is a bit of a shock to me as I consider that such wire boxes are not adequate enough or diverse enough to be called aviaries. This brings up the issue of when is a cage a flight and when is a flight an aviary?

Obviously the cage is an enclosure of limited size and although more portable, can be restrictive for the parrot; the second is usually a longer, narrower area offering hookbills the pleasure of full flight, even if sometimes in a straight line back and forth; while the third is often used interchangeably with a flight, but suggests an even larger space with many lifestyle enhancements designed for the gratification of the occupying birds and for pleasing the eye of the beholder.

Now that is not to say that every cage must necessarily be boring and uninviting for its parrot. Many pets in a home prefer to eat, sleep, nap, chew, and just hang out in the security of their own cage. Where cages lack sufficiency, is usually in the realm of potential exercise. There just is not enough room to burn off calories at the high rate natural to avian species. Climbing for birds is like crawling for humans and has few cardio-vascular benefits, whereas flying for avian species is like running for humans, strenuous, athletic, and beneficial.

Buy Now!

By David Waugh Correspondent, Loro Parque Fundación

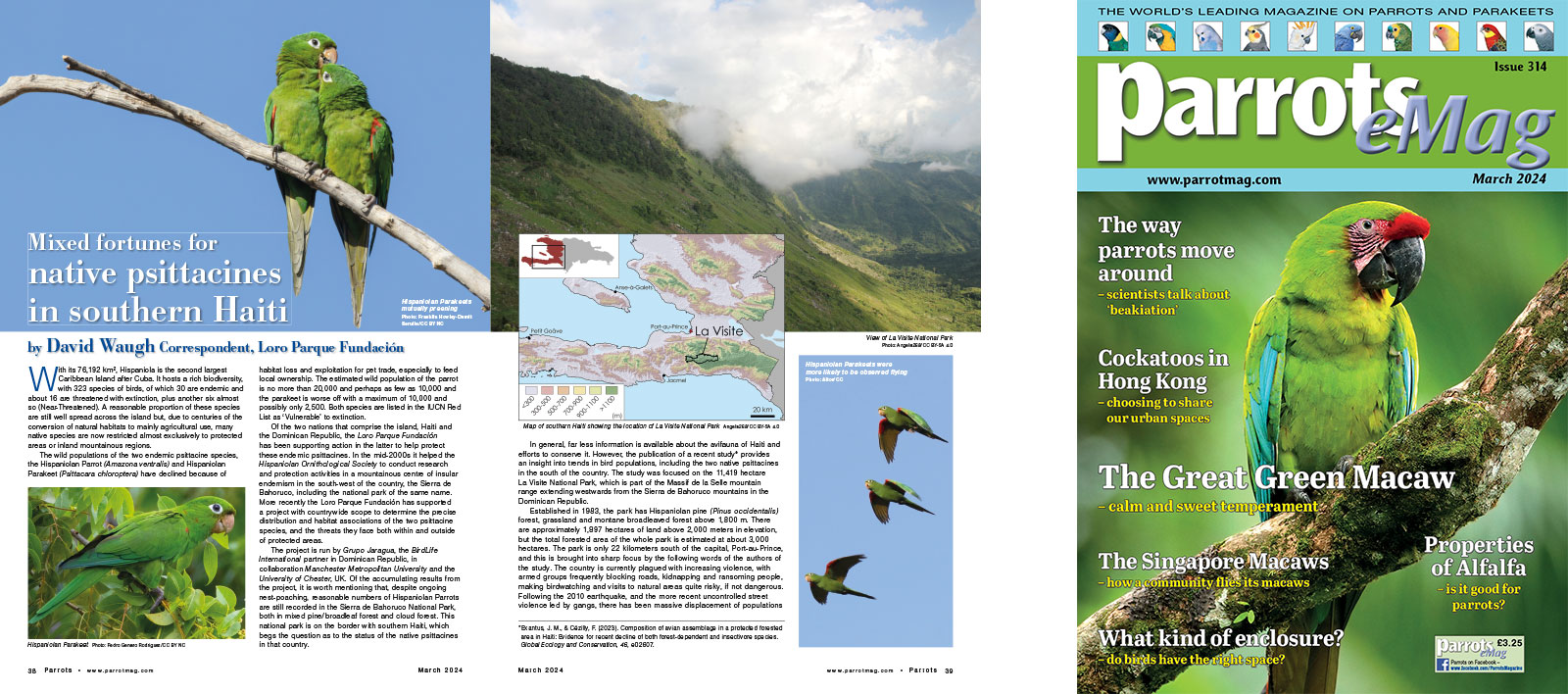

With its 76,192 km², Hispaniola is the second largest Caribbean Island after Cuba. It hosts a rich biodiversity, with 323 species of birds, of which 30 are endemic and about 16 are threatened with extinction, plus another six almost so (Near-Threatened). A reasonable proportion of these species are still well spread across the island but, due to centuries of the conversion of natural habitats to mainly agricultural use, many native species are now restricted almost exclusively to protected areas or inland mountainous regions.

The wild populations of the two endemic psittacine species, the Hispaniolan Parrot (Amazona ventralis) and Hispaniolan Parakeet (Psittacara chloroptera) have declined because of habitat loss and exploitation for pet trade, especially to feed local ownership. The estimated wild population of the parrot is no more than 20,000 and perhaps as few as 10,000 and the parakeet is worse off with a maximum of 10,000 and possibly only 2,500. Both species are listed in the IUCN Red List as ‘Vulnerable’ to extinction.

Of the two nations that comprise the island, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, the Loro Parque Fundación has been supporting action in the latter to help protect these endemic psittacines. In the mid-2000s it helped the Hispaniolan Ornithological Society to conduct research and protection activities in a mountainous centre of insular endemism in the south-west of the country, the Sierra de Bahoruco, including the national park of the same name. More recently the Loro Parque Fundación has supported a project with countrywide scope to determine the precise distribution and habitat associations of the two psittacine species, and the threats they face both within and outside of protected areas.

Buy Now!

By Rosemary Low

The Great Green Macaw (Ara ambiguus) is not only an extraordinary handsome and imposing bird, it also has a lovely calm and sweet temperament, quite different to the Military. I worked with a breeding pair at Palmitos Park in Gran Canaria and I always loved this species. It is often confused with the Military Macaw (Ara militaris) which is smaller and darker in colour.

Among the large macaws, the Great Green – often called Buffon’s Macaw - tends to be overlooked. Unlike the Scarlet or the Green-winged, it has little red in its plumage and it lacks the dazzling brilliance of the Hyacinth. But I see it as a majestic bird. The Great Green, Hyacinth and Green-winged Macaws (Ara chloropterus) are the three largest parrots in the Neotropics (South and Central America).

The Great Green (Ara ambiguus), the Blue-throated (Ara glaucogularis) and the Red-fronted (Ara rubrogenys) are the most endangered of the large macaws, being the only ones listed as ‘Critically Endangered’ by the IUCN.

Buy Now!

By GrrlScientist, Senior Contributor, Evolutionary & behavioural ecologist, ornithologist & science writer

If you’ve lived with parrots all of your life, you are no doubt familiar with the variety of methods they use to get from place to place. One such method that is now getting attention from scientists is a method they’ve named ‘beakiation’. This method of moving from branch to branch, along one thin branch or even along a grass stem by alternately using their beak and feet was named in honour of ‘brachyation’, a method that primates use to move in trees by swinging from branch to branch using their arms.

In this study, three researchers at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine report that Rosy-faced Lovebirds (Agapornis roseicollis), also known as the Peach-faced lovebird, a common pet throughout the world, use a novel method of getting around on thin twigs. The main focus of this inquiry was to measure the energy used to beakiate.

“Parrots are specialised for climbing and moving around in the trees,” said evolutionary biomechanist Michael Granatosky, a professor at NYIT whose expertise is understanding the origins of quadrupedal locomotion. As part of his ongoing studies, Professor Granatosky and collaborators previously investigated how parrots can use three limbs to get around, thereby violating the ‘forbidden phenotype’ (more here). As a follow-up to that work, Professor Granatosky wondered what would happen if you flip a bird upside down or make them move on the tiniest branch possible?

Buy Now!