by Megan Myers

The methods described here are based on birds following basic commands, and will help when releasing parrots into the wild.

A training technique that has been practised by parrot owners for decades is now being applied by Texas A&M University researchers in establishing new bird flocks in the wild.

While many parrot owners clip their birds’ wings to reduce their flight abilities, free-flight involves training an intact parrot to come when called, follow basic commands, recognise natural dangers, and otherwise safely fly in open areas.

In a recently published paper in Diversity 2021, Constance Woodman, a doctoral graduate student of the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVMBS), and Donald Brightsmith, a CVMBS associate professor, shared their findings from a project with Chris Biro, a globally recognised free-flight trainer. This project included documenting Biro’s training process step by step so that conservationists can apply his methods when releasing birds into the wild.

Buy Now!

Complete Psittacine by Eb Cravens

I have known for a long time that psittacines will eat in cycles, going from certain dietary items to other items over weeks or months depending upon their bodily needs. Some keepers will misinterpret such tendencies as those of ‘picky eaters’ when in fact it is a manifestation of the intelligence in birds to sort through a variety of nourishment seeking things most important to their metabolism at that specific time. That is why it is necessary to give green stems and raw veggie bits every day, so that one can ascertain exactly when members of the flock are seeking out specific enzymes and phytonutrients.

I first observed birds in my care choosing carefully what to eat about 30 years ago when I had breeding Princess of Wales Parakeet pairs in a large colony flight planted with trees and foliage of all kinds. We were growing chard and kale greens on the ground for forage material. During the first days after Gracie and Charming had had a successful clutch hatch, I went out in the morning and saw some of the greens plants with all the leafy portions nibbled off leaving bare leaf ribs and veins attached to the plant. I thought this was unusual and rather selective of the new parents that they were choosing to avoid the stems and only eat the leaf.

You can imagine my surprise when about seven days later during the nest box chick feeding, I discovered other kale plants with rings of discarded leafy material around the plants and all of the stem material consumed right up to the stalk. Talk about choosing your nutrients!

Buy Now!

by Andrew Stafford

Nearly a century after the extinction of the Paradise Parrot, a tiny team is trying to protect its cousin, by using land clearing. In 1922, Cyril Jerrard captured the first and only photographs of the Paradise Parrot, the only Australian bird to be officially declared extinct since European colonisation. Jerrard was well aware he was looking at one of the last of its kind and wrote in 1924, “The one undisguisable fact is that the advent of the white man has spelled destruction to one of the loveliest of the native birds of this country.”

The last accepted sighting of a Paradise Parrot, also by Jerrard, was in 1927 near Gayndah in the Burnett River district of southern Queensland. Nearly a century later, in the fading light of dusk, I’m standing 20 metres from a bird feeder, clicking away in vain as a pair of Golden-shouldered Parrots, the Paradise Parrot’s closest surviving relative, accept a handout at Artemis Station, a cattle property on the Cape York Peninsula in the state’s far north. My images are rubbish, but while I’m watching, I have an eerie sense of how Jerrard might have felt.

Almost exactly 10 years ago, I watched a flock of 50 Golden-shouldered Parrots beside the Cape Developmental Road at Windmill Creek, near the northern boundary of Artemis. For decades, the 125,000ha station has been the species’ stronghold. Today it holds, maybe, 50 birds in total. There are scattered groups on neighbouring stations, and an unknown number in the remote Staaten River National Park to the south.

Buy Now!

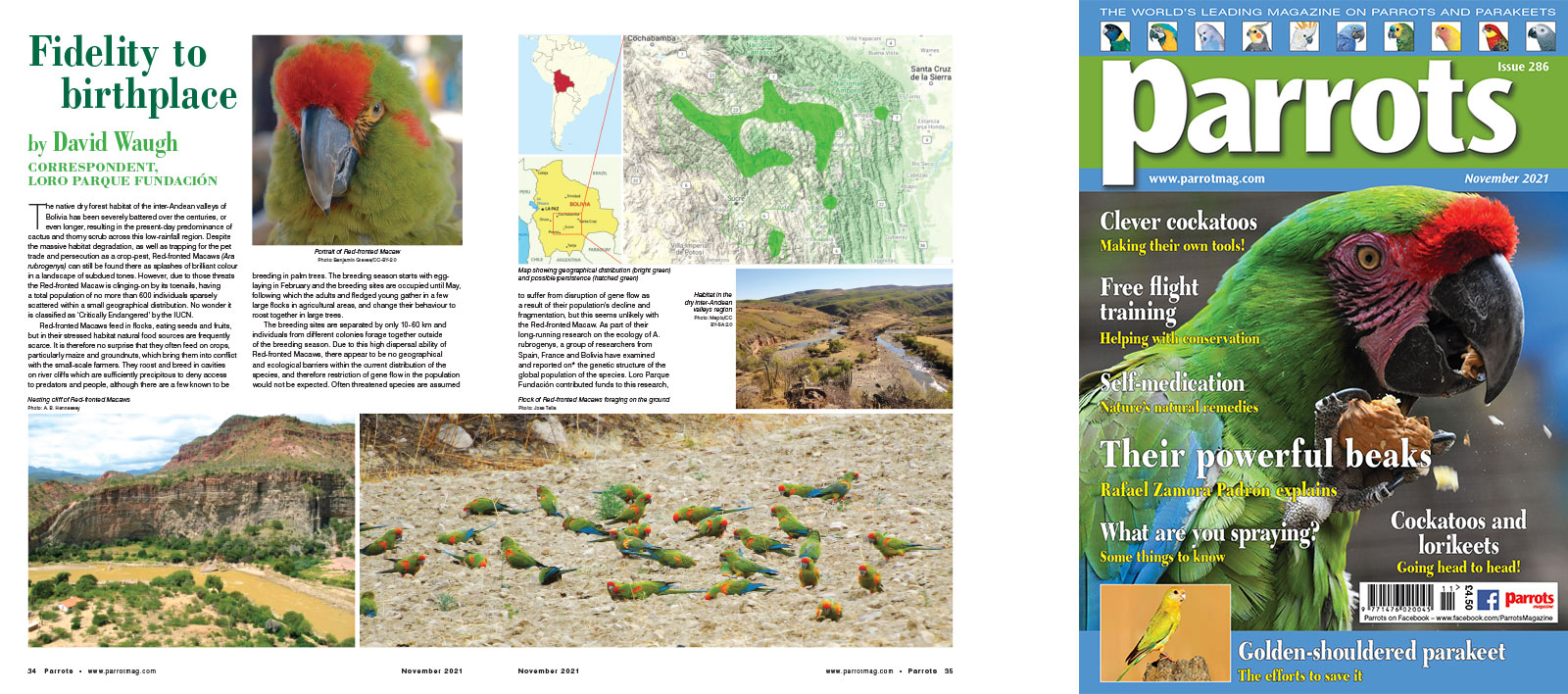

by David Waugh, Correspondent, Loro Parque Fundación

The native dry forest habitat of the inter-Andean valleys of Bolivia has been severely battered over the centuries, or even longer, resulting in the present-day predominance of cactus and thorny scrub across this low-rainfall region. Despite the massive habitat degradation, as well as trapping for the pet trade and persecution as a crop-pest, Red-fronted Macaws (Ara rubrogenys) can still be found there as splashes of brilliant colour in a landscape of subdued tones. However, due to those threats the Red-fronted Macaw is clinging-on by its toenails, having a total population of no more than 600 individuals sparsely scattered within a small geographical distribution. No wonder it is classified as ‘Critically Endangered’ by the IUCN.

Red-fronted Macaws feed in flocks, eating seeds and fruits, but in their stressed habitat natural food sources are frequently scarce. It is therefore no surprise that they often feed on crops, particularly maize and groundnuts, which bring them into conflict with the small-scale farmers. They roost and breed in cavities on river cliffs which are sufficiently precipitous to deny access to predators and people, although there are a few known to be breeding in palm trees. The breeding season starts with egg-laying in February and the breeding sites are occupied until May, following which the adults and fledged young gather in a few large flocks in agricultural areas, and change their behaviour to roost together in large trees.

Buy Now!